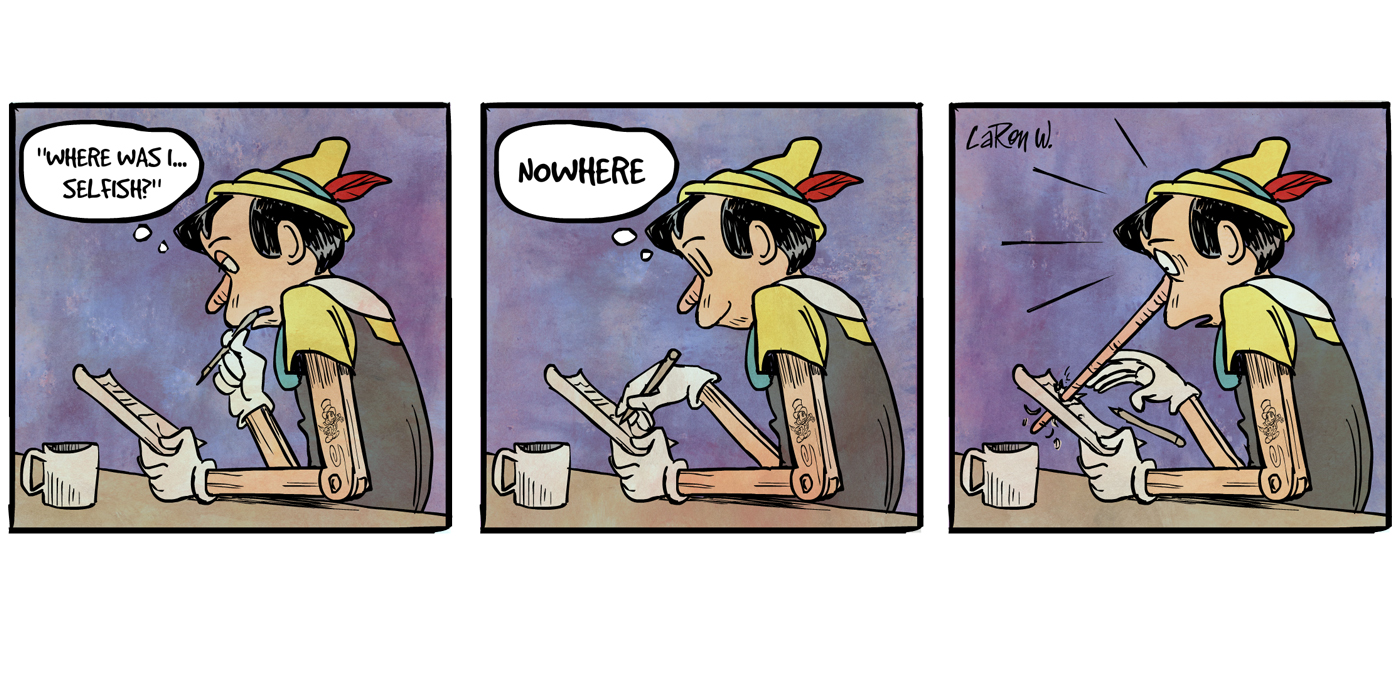

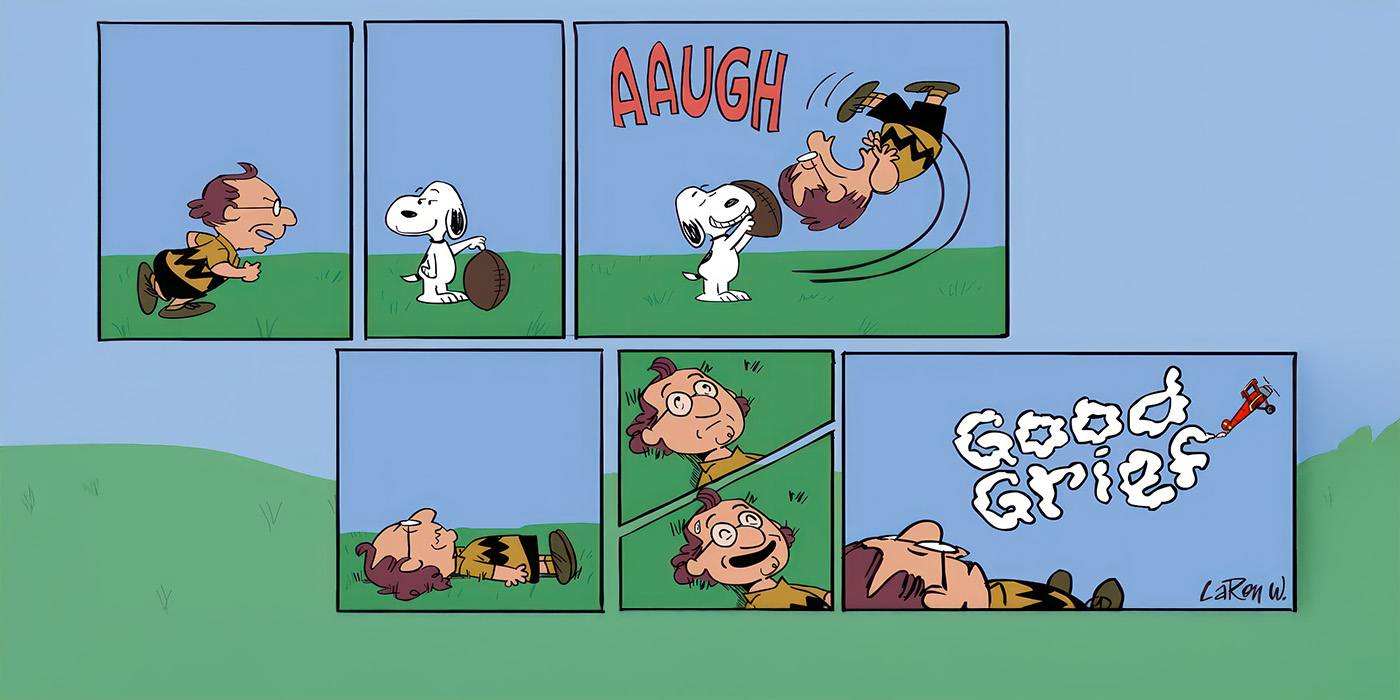

In my memory, the expression “good grief” was a common expletive of the cartoon characters in Peanuts. For much of my life, I used “good grief” to express astonishment, dismay, and frustration, never considering the deeper truth hidden within the euphemism. Before I entered the SA program (10/21/1998), I lived with an accumulation of frozen grief. Only after a couple of journeys through the steps did I begin to understand and embrace the benefits of grieving. I realized that journeying through grief was healing and good for me.

When I was 14, a close uncle committed suicide, a victim of unresolved WWII PTSD. At 16, my oldest brother, age 22, died unexpectedly from a brain aneurysm. Those

close, unexpected deaths shocked me deeply—my first experiences of grief. I felt grief had ripped my young, aching heart wide open. With both occurrences, I emotionally lost control of myself. I was ashamed of my behavior, of being heartbroken and in tears. I resolved to better control my emotions around grief.

During the next fifteen-plus years, I lost several peers. I lost two of my closest friends, three other school friends, two cousins, and a younger neighbor, all to suicide. Another schoolmate died of a brain tumor, and five schoolmates died in vehicle-related accidents. Grief became something to suppress. I strove to minimize the pain and get through it as quickly as possible. I did not realize that the unmourned grief was retained, frozen in my body and my psyche, and that I was becoming increasingly cold-hearted. Before long, I felt nothing when I heard someone had died or had been killed. Worse, I was becoming progressively mean-hearted.

My mother died when I was 32; she was the first person I allowed myself to grieve. During that time, I also grieved my brother, who had died sixteen years earlier. I experienced relief; I allowed myself to feel the love and the pain of family loss. The experience of grieving set the stage for future 12 Step work. However, at the time, I did not allow myself to emotionally go near the past or other accumulating deaths.

Curiously, before entering SA, every fall beginning around the last two weeks of October, sometimes lasting through November, I would experience what I called my dark month. A depression would come over me. It was about 15 years before I even recognized the repetitive pattern. The unmourned grief remained within for nearly 30 years. Needless to say, not grieving became a contributing factor to the progression of my sex addiction. Withdrawal into a fantasy life became my solace for escape.

Finally, about four years into SA recovery, one November I began talking about grief with my sponsor, my first close friend in many years. I began by relating the relief I had experienced in mourning my mother. During weekly discussions, I began naming and afterward counting the suicides and the number of deaths. Of the sixteen peer deaths in fifteen years, thirteen of them were male; this deeply influenced my behavior, especially when it came to nurturing friendships with men. I withdrew from close relationships. I hid my feelings and withdrew inward, hiding from uncomfortable people, places, and things.

I became aware that I had built what in recovery I now call a protective ceramic armor around myself; happily, it had cracks that allowed some emotions in. Nevertheless, locked within that self-made ceramic prison were “guilt, self-hatred, remorse, emptiness, and pain,” and I retreated “ever inward, away from reality, away from love,” until I had become almost completely “lost inside” myself (SA 203).

In recovery, I practiced naming the individuals, fondly remembering them for who they were, sharing with others who were safe, and offering prayers for those departed. In grieving, I learned that the pain of loss slowly dissipates until only love remains. Grieving helped me release aspects of my addiction, as well as my survivor’s guilt. I learned to be compassionate, and with continued step work, I slowly became warm-hearted and risked friendships with other men.

Grieving, in my experience, has a beginning, a middle, and a soft open ending (I still pray for my friends and loved ones). In doing Step work, I became more willing to surrender character defects. I have become increasingly grateful for my recovery and even for being a sexaholic. On a daily basis, I am now more “entirely ready” (Step Six) “to turn [my] will and [my life] over to” my Higher Power (Step Three), because I know that despite my fear and resistance, greater relationships, greater love, and greater freedom are the fruit (SA 208). “Good grief”: I can now “look the world in the eye and stand free” (SA 205).

Jack H., California, USA